Can Japan’s legendary savers spark a stock market boom?

Simply sign up to the Japanese business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

There are roughly 325,000 married women in Japan with the family name Watanabe. The country has about the same number of Mrs Itos, significantly more Mrs Suzukis and almost twice as many Mrs Satos.

But for some reason and for some decades, Mrs Watanabe has been the one chosen to stand as the symbolic byword for all Japanese households — a mythical matriarch credited with key decision-making powers and executive control over the family purse-strings.

Over the years since Japan’s “miracle” growth period in the 1970s and 1980s, Mrs Watanabe’s financial firepower has been the stuff of fascination for everyone from local bank managers and backstreet gold retailers in Japan to bond traders on Wall Street. Today, more so than ever, everyone wants to know Mrs Watanabe’s next move.

Even after 30 lean, post-bubble years, Japanese households hold ¥2.1 quadrillion ($14.7tn) of financial assets, of which more than half ($7.7tn) is held in cash and deposits. By contrast, households in the US and UK respectively hold 13 and 31 per cent in deposits.

In national terms, Japan’s cash savings alone are equivalent to the combined annual gross domestic product of Germany and India. In corporate terms, Mrs Watanabe could buy Apple, Microsoft and Saudi Aramco with what she has sitting (earning almost zero interest) in the bank.

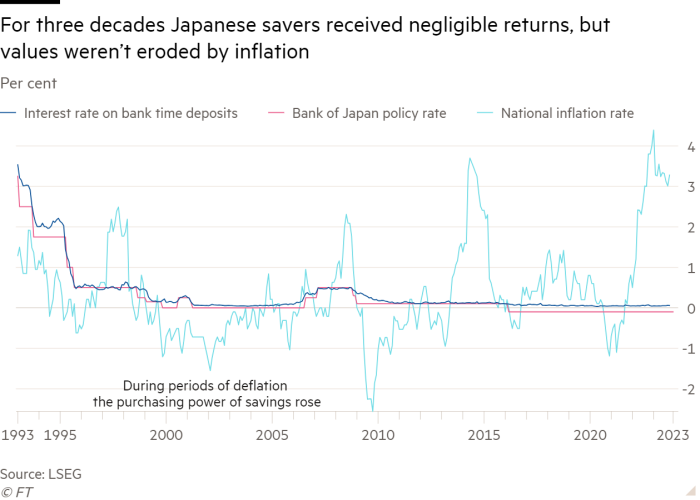

When prices in Japan were stagnant or falling, as they were for most of the past 25 years, Mrs Watanabe’s preference for holding the majority of savings in cash was reasonable, especially so after the government guaranteed bank deposits in 1995.

The central bank’s long experiment with ultra-low interest rates, which began in the late 1990s, meant she was not making any returns, but nor was her wealth being significantly eroded as long as Japanese companies held back from raising prices.

But as more and more Japanese companies have broken ranks and raised prices in the past couple of years, Mrs Watanabe has arrived at a pivotal moment.

“If she’s losing value on her cash, Mrs Watanabe is going to have to do what the rest of the world does and go into real assets like equities or property,” says Peter Tasker, a Tokyo-based analyst at Arcus Research.

After years of failed efforts to coax that exact switch into investment, the Japanese government has created an unprecedented inducement. From January 2024, a dramatically expanded version of the Nippon Investment Savings Account, or Nisa, will offer a remarkable lifetime tax exemption for individuals’ equity investments. They have also raised the limit on both annual contributions from ¥1.2mn to ¥3.6mn and the cumulative limit from ¥6mn to ¥18mn.

If the ploy works, it will begin to offset an aversion to stocks that has bedded-in since the collapse of the 1980s stock bubble. Japanese households hold just 24 per cent (17 per cent direct and 7 per cent through their pensions) of their assets in equities — far lower than the 54 per cent in the UK and 75 per cent in the US.

That sets up, over the coming weeks and months, one of the biggest questions ever asked of the Tokyo stock market, its constituent companies and of Mrs Watanabe.

Are savers about to become serious, price-moving retail investors in a domestic Japanese stock market that they have long shunned like a casino? Even a relatively moderate positive answer and a mere 2 per cent reallocation of assets, say analysts at AllianceBernstein, could produce $150bn of inflows into equities. If that happened, it would be market moving, say brokers. Inflows of less than half of that from foreign investors triggered a rally of more than 25 per cent in the Topix this year.

“I don’t know if I necessarily represent the average Japanese household, and I don’t think our savings are as big as you think,” says Chieko Takenaka (née Watanabe), a retiree living in Kanagawa prefecture.

“But I can tell from talking to my friends on the chat group that we are all thinking about the same sort of things when it comes to rising prices and how to deal with that. I’m definitely scared of losing money in stocks, but I think our biggest worry is having enough money if we live another 20 years.”

In mid-December, an unusual advert appeared in Japanese trains entreating people to buy new shares being issued by Denso, the country’s largest car parts manufacturer. As the advert hopefully made clear, say two bankers involved in the deal, the target of the sale was Mrs Watanabe and the new space for stock investment created by the Nisa programme.

But will such marketing work? The Mrs Watanabe shorthand only goes so far. Many of the habits and decisions broadly ascribed to “Mrs Watanabe” are those of a minority of households. Japanese people who grew up in the “lost decades” of the 1990s and 2000s are less likely to be married or have children than their parents at the same age and they have not had much money to save.

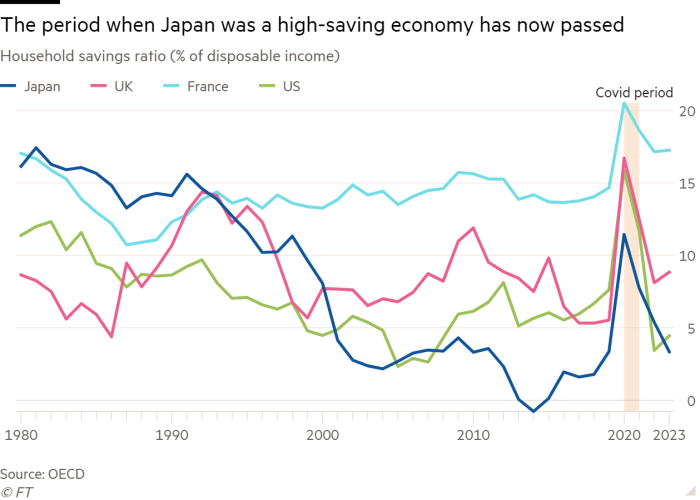

The celebrated $7.7tn cash pile belongs principally to the middle-aged and elderly. Japan’s household savings rate fell from about 17 per cent of disposable income in the early 1980s to about 3 per cent by the early 2000s.

“The fabled high savings rate of Japanese households is long gone,” says Richard Katz, author of The Contest for Japan’s Economic Future. “Instead, people are sustaining consumption as best they can by spending larger and larger portions of their stagnating income.”

Still, the Mrs Watanabe trope has an important value, say economists. Particularly now as the nation decides whether to believe that, after years of false dawns and empty reassurance from political leaders, it is finally time to shed the deflationary mindset that has long defined decision-making.

There is a strong case for believing that now is the time. Even if the rate of inflation falls back from current levels, it has spent more than 18 months above the Bank of Japan’s target of 2 per cent and the historic abnormality of that is starting to hit.

Many economists talk of a “regime change”. A normalisation of Japan’s still ultra-loose monetary policy looks possible for the first time in many years. The Japanese stock market has risen strongly through 2023, with much of that driven by the perception that the Tokyo Stock Exchange itself is pushing companies to become more investible.

“The collective scar tissue from three decades of underperformance by Japanese equities is not going to disappear overnight. But if inflation persists then Japanese households will at some stage need to reposition into assets that can generate higher yen-denominated returns,” says Bruce Kirk, Japan equity strategist at Goldman Sachs.

Inevitably perhaps, a brisk trade has sprung up to anticipate and even encourage a historic change in investment behaviour.

This year, under an onslaught of marketing, individuals have opened more than 2.5mn new accounts at the nation’s three largest online brokerages, seemingly in preparation for the new Nisa scheme. The fact that during 2023 Berkshire Hathaway, whose head is the legendary investor Warren Buffett, increased its investment in five Japanese stocks has for many provided an important vote of confidence.

In August 2022, Japan’s largest brokerage, Nomura, took out a prominent newspaper advert which not only declared that inflation had now become part of normal life in Japan, but included the eye-catching assertion that “not responding to change has finally become the risk”.

The preparations by brokerages have uncovered distortions caused by the long disdain of domestic stocks. Older sales staff in a suburban Tokyo branch of one of the largest securities houses in Japan told the Financial Times they had found themselves talking to 30- and 40-year old colleagues who had never once sold a Japanese equity product.

But there is real enthusiasm building. Yusuke Nishikawa, a managing director of product development at Nomura in Tokyo, says that in 20 years of working for the company, this is the most excited he has ever seen clients. For a long time, Japanese equities were a hard sell. “But now there are many positive things, such as reform by the [Tokyo Stock Exchange] and wage increases which are future-oriented. It has been a long time since we were able to recommend Japanese stocks in the way we are today,” says Nishikawa.

The buzz is reflected on the shelves of Japanese bookstores. They are crammed with volumes offering a crash course in financial literacy. Book titles swerve between enticement — How to Achieve a Privileged Life! — and warning — Are You Prepared for What is to Come? — with an increasing number detailing how to extract maximum value from the Nisa scheme.

And in that latter group, much of the writing is built around trying to show that equities tend to flourish under inflationary conditions, and as such, represent something relatively safe. But scepticism is hard-wired. In the 1970s, Japanese individuals owned 40 per cent of the Japanese stock market. After stocks peaked and then crashed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, that ratio began to sink towards its current level of just 17.6 per cent.

In 2014, Japan introduced a limited version of the Nisa, modelled on the UK’s Individual Savings Account scheme. Since then, more than 20mn accounts have been opened, with about ¥34tn invested in them. But, as AllianceBernstein analyst Rupal Agarwal notes, the scheme remains underutilised and only 17 per cent of the total population hold accounts. The new Nisa scheme will triple the upper limit of annual investment to ¥3.6mn.

If the government is successful in its target of 34mn new accounts opening in five years, the total flow into equities could run into the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Many brokerages are betting that most of the buying will focus on index trackers and passive funds. Some, though, have begun to lay out the more specific stocks and themes that Mrs Watanabe might go for.

Of particular interest, says Masatoshi Kikuchi, chief equity strategist at Mizuho Securities, may be the 1,463 different listed companies that offer “shareholder benefit schemes” — offers of food products, cash-equivalent prepaid cards and other perks.

One of the key reasons that Kikuchi believes shares in the supermarket chain Aeon are trading on a forward price-to-earnings multiple of 100x compared with just over 20x at its rival Seven & i Holdings is because Aeon distributes benefits cards to shareholders offering store discounts. Similarly, shareholders of Oriental Land receive a one-day passport to Tokyo Disneyland.

“Although not many major companies appear to be newly adopting a shareholder benefits plan . . . there are deep-rooted expectations that individual investors will choose stocks with shareholder benefits plans for their Nisas,” says Kikuchi.

Stefanie Drews, president of Nikko Asset Management, says that the most significant challenge will lie in bridging the stark divide between those with investment experience and those with none at all.

Only about 20 per cent of Japanese individuals can currently be considered investors, she says. “Meanwhile, Nisa has the potential to be a major catalyst to motivate the remaining 80 per cent to consider starting to invest.”

Drews notes, however, that generational differences will be pronounced. Many younger households learn to invest through social media.

One key influencer is Hasen Kuniyama, a 32-year-old YouTuber who co-presents an investment show called Money Skillset, which can draw more than a million views per episode. In the show, Kuniyama discusses a range of issues around Nisa and other investment strategies with Rintaro, a comedian who, in effect, plays the role of Mrs Watanabe, asking the questions of a relative novice.

The levels of interest in the show, particularly among younger Japanese, have been far beyond what Kuniyama expected. As has the strength of feeling around the generational wealth gap and the possibility that investment may provide some way of reversing that.

Japanese people under the age of 40 look at older generations and see that they reaped great financial benefit from the bubble economy, Kuniyama says. Young people want to work hard, become members of society and help make Japan prosperous, but many also feel the economy is closed off to them. “I think that is why a lot of them watch,” he says.

For all of the hype building around the Nisa scheme there are, say Kuniyama and others, significant reasons why it may fall short of expectations, with the buy-in by Mrs Watanabe more of a slow burn than a big bang.

“There is a deep-rooted scepticism about the economy,” says Stefan Angrick, senior economist at Moody’s Analytics. “Decline has been a feature of life that people see and hear about all the time, and over a long period. Whether it comes in the form of talk about the weak yen, the falling population or China overtaking Japan, the same theme keeps coming back.”

There is also a specific mistrust of Japanese equities, say brokers. Many Japanese individuals work for Japanese companies and a common perception is that businesses are not primarily run for the benefit of shareholders. They are not necessarily seen as an attractive place to put money.

A senior executive at one of Japan’s largest online brokerages describes a recent lecture session in rural Japan that allowed the public to ask anything they wanted about the Nisa scheme. “One person stood up at the lecture and effectively asked us whether we thought he was stupid,” says the executive. “Warren Buffett, said the man, had only been buying Japanese stocks so he could make his money and sell them back to retail Japanese investors. The scepticism runs very deep.”

One possibility is that Japanese people will use the expanded Nisa scheme and its lifetime tax exemption not to buy Japanese equities but to buy yen-denominated products that give households exposure to US equities, say brokers and asset managers. In particular, the S&P 500 index.

“The Nikkei 225 has been rising quite a bit, so some people are taking a positive view of it,” says Kuniyama. But he notes the disproportionate appeal of the S&P 500. “Personally speaking, I think that young people in their twenties and thirties just do not have very high expectations for the future of Japan.”

Paul Sheard, author of The Power of Money, says that the Japanese stock market would essentially answer two questions over the coming months.

The first is whether the sense of mild deflation is still embedded in people’s minds. Shaking it off, even with months of inflation, can be very, very difficult he says.

Second, on whether Mrs Watanabe will buy domestic stocks, another set of issues are in play, he says. The average Japanese household is not particularly engaged because they have no reason to be.

“They are swimming in waters where the elites appear to be managing the whole thing — chastising the household sector for not ramping up their inflation expectations, and chastising companies for not raising investment or wages,” says Sheard.

“Japanese households are being told to raise their inflation expectations now, and the household is going, ‘I’ve been told this [other thing] for 25 years, and I don’t quite believe [the new instruction].’

“So with Nisa, you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink,” he adds. “A lot of people are going to be saying, ‘Where’s the catch?’”

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

Comments