Global shocks put Africa’s resilient spirit to the test

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It has been common to regard economies in Africa as more vulnerable to disruption than other regions. The finances of governments, businesses and individual citizens alike have been battered by external shocks ranging from Covid to food inflation stemming from the war in Ukraine and the altered global interest rate landscape. Bank lending to smaller African enterprises remains prohibitively expensive.

The Institute for Security Studies estimates that 30mn people dropped into extreme poverty — defined as living on less than $1.90 a day — as a result of the Covid pandemic. Zambia and Ghana have defaulted on debt, hinting at possible trouble ahead in other countries.

But another line of thought has it that, despite the concerns, African economies — with their large informal sectors and family support networks — are more resilient than pessimists give them credit.

“The idea that, for every problem in the world, Africa is the next victim is not necessarily so,” said Donald Kaberuka, former president of the African Development Bank, at a forum last month in Nairobi, organised by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

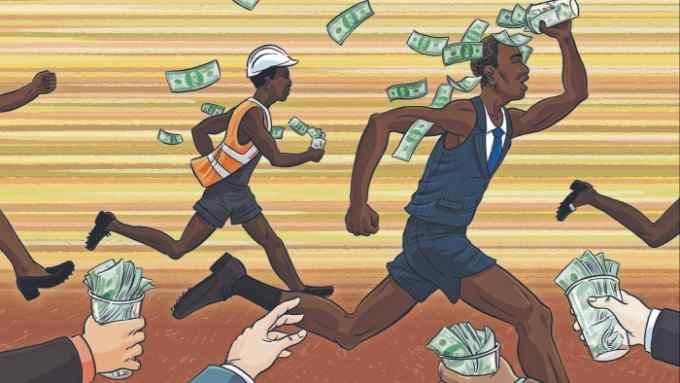

One possible measure of that resilience is the entrepreneurial flair and the roster of fast-growing companies that continue to emerge from the continent. The FT-Statista 2023 annual ranking of Africa’s fastest-growing companies is an attempt to capture some of that dynamism.

The ranking, now in its second year, judges companies according to their compound annual growth rate in revenue between 2018 and 2021. Its methodology, which does not factor in the cost of acquiring customers or a company’s profitability, typically favours start-ups over more established businesses.

And this year’s results suggest that businesses in sectors including fintech, renewable energy, healthcare, commodities and, to some extent, agriculture were managing to grow while much of the world shut down.

As in the ranking’s inaugural year, Covid appears to have accelerated a move online, with companies providing digital services in finance, payments, trade facilitation and healthcare all making headway.

It also seems to have been the time in which Silicon Valley investors, as well as those in Asia and Europe, discovered potential in the African start-up scene, particularly in the tech hubs of Lagos, Cape Town, Johannesburg, Nairobi and Cairo.

“A lot of my friends . . . in Silicon Valley were getting FOMO [fear of missing out] about Africa,” says Steve Beck, co-founder of Novastar Ventures, a Nairobi-based venture capital firm. “They were starting to put money to work on the continent, flying in and out, and pushing up valuations.” Beck notes that figures from the Paris-based tech and digital investment platform Partech show African tech start-ups raised $5.2bn in 2021 — three times more than the previous year.

That drove up valuations, attracting yet more capital, though there are signs that the market has cooled considerably this year — a period not covered in the ranking — partly as a consequence of the run on Silicon Valley Bank.

Two Nigerian companies top the latest list. Abuja-based AFEX Commodities Exchange, which provides brokerage and trade finance services for commodities such as maize, sorghum, cocoa and rice, is in first position, with a compound annual growth rate over three years of more than 500 per cent.

Moniepoint, a Lagos-based company that offers banking for small businesses, rates second. Novastar was an early funder.

Third is Kenya’s Wasoko, which headed the list in the previous year. Set up in Nairobi, the ecommerce company helps small traders access inventory through more efficient supply chains in seven African countries. It has recently opened an office in Zanzibar, which is seeking to attract start-up business.

About a third of Africa’s fastest-growing companies, according to the new ranking, are in South Africa — still the continent’s most sophisticated economy, in spite of low growth and persistent power shortages. Mining and metals companies dominate, but other South African companies that make the list are in the renewable energy, software and healthcare sectors.

As in the inaugural year, start-ups feature strongly, but do not monopolise. More established companies in the mining sector — driven largely by demand for the metals needed for the energy transition — as well as in telecoms and construction also make the top 100. Outside mining, there is a dearth of exporters, particularly of value-added products, on the list.

Kaberuka says that making the 2018 African Continental Free Trade Area agreement work is key to bolstering the environment for companies that make and export goods: “Integration is never easy,” he points out. “Ask the Europeans. But it is a problem that we have to work on.”

Hafou Touré, the founder of Abidjan-based HTS partners, which advises small and medium companies on growth strategies, says another big problem for start-ups with regional ambitions is accessing capital. Investment priorities are skewed by foreign investors, she says.

“We don’t really have love-money capital. When you look at the capital coming into start-ups you’ll see that the money is coming from outside,” she says. “We also need local capital.”

Fintech and IT and software sectors dominate the ranking, but a feature of the top 100 is the variety of corporate activity. Fastest-growing companies include a Namibian winery, a Kenyan fish farm, a South African company that conducts remote-hearing tests and renewable energy companies in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone.

However, Aubrey Hruby, co-founder of the Africa Expert Network and an investor in early-stage African companies, questions the methodology of a list that can include both big established companies and start-ups, where fast growth from low levels of revenue is easier. “You can’t be comparing mining companies with Moniepoint,” she argues, referring to the Nigerian fintech business.

As in the inaugural year, though, the list — which was compiled with Statista, a research company — is an exercise in approximation and does not claim to be definitive. But the screening process, which requires senior executives to sign off on the figures submitted should mean the ranking offers a helpful guide to the companies and sectors that are managing to do business in a complex and fast-changing environment.

This story was amended after first publication to correct the name of the company Wasoko

Comments